- This event has passed.

Carving Out a Niche Under the Storm – by China Daily with content from the Interview with Glendy Choi, Founder of LBA

May 27, 2022

The original article was published in the “CHINA DAILY” on Fri 27 MAY 2022

Joshua Lau, a 20-year-old with autism and mild intellectual disability, has done well among his peers by receiving two job offers from local bakeries.

In the days before the COVID-19 pandemic, that was not a big deal, but after living in the shadow of the disease for two years, it is considered a big achievement for Lau.

That’s because four in every five young people with special education needs cannot find jobs as a result of the sluggish economy and insufficient vocational training caused by the pandemic.

The secret to Lau’s success was a decision made by his father Wallace Lau, who opted to send his son on a new program for SEN students at the Education University of Hong Kong in 2019.

Joshua Lau joined the university from a vocational training center, becoming one of the more than 40 SEN students who comprised the first batch of such people to study together at the college.

The father wanted his son to study more than just vocational skills — things such as liberal education, cutting-edge knowledge and interpersonal skills, just like his able-bodied peers.

Young people with special education needs seek to live independently despite worsening job prospects under the pandemic. Oasis Hu reports from Hong Kong.

The effects quickly became apparent. After just a few months, the young man’s abilities had improved on all fronts: he was better at expressing himself; was more outgoing, focused and creative; and more willing to interact with other people.

Most of the changes were attributable to his eventful college life.

For the ecology course, Joshua Lau visited a private farm to learn the names of plants. Meanwhile, he learned to compose via computer software in the music course, appreciating the creation of art and beauty. In the career-planning class, he listened to outstanding SEN students who had been invited to give confidence-building speeches.

In his spare time, he played the piano, painted and took part in ice-skating competitions and volunteer activities.

He also made friends, which was hard to do at the vocational center.

In the university’s cafeteria, he helped a visually impaired classmate by keeping him close, helping carry his lunch tray, providing assistance when he ordered food, and finding seats.

According to Wallace Lau, the pandemic has left an indelible mark on SEN students, especially on those who began their three years of training in 2020, because their career prospects have been severely hit.

Growing Numbers

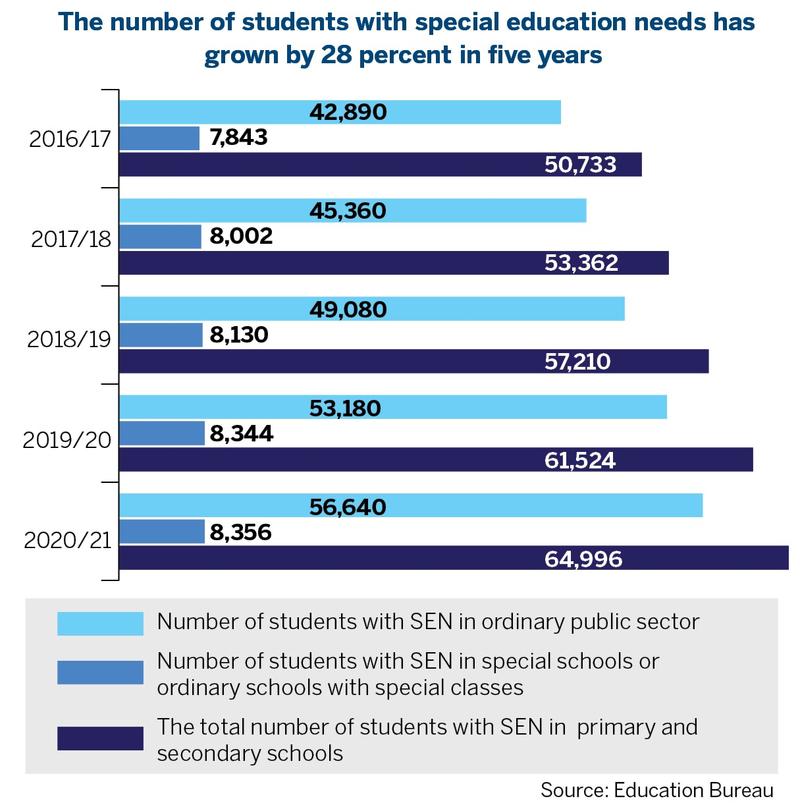

There are more than 70,000 SEN students in Hong Kong. As the city government has promoted integrated education over the years, assessments for SEN students have been expanded, and their exact number has risen.

In 2000, there were 3,000 people with autism in Hong Kong, but that number had risen to 130,000 by 2021, according to data from social organizations for SEN students.

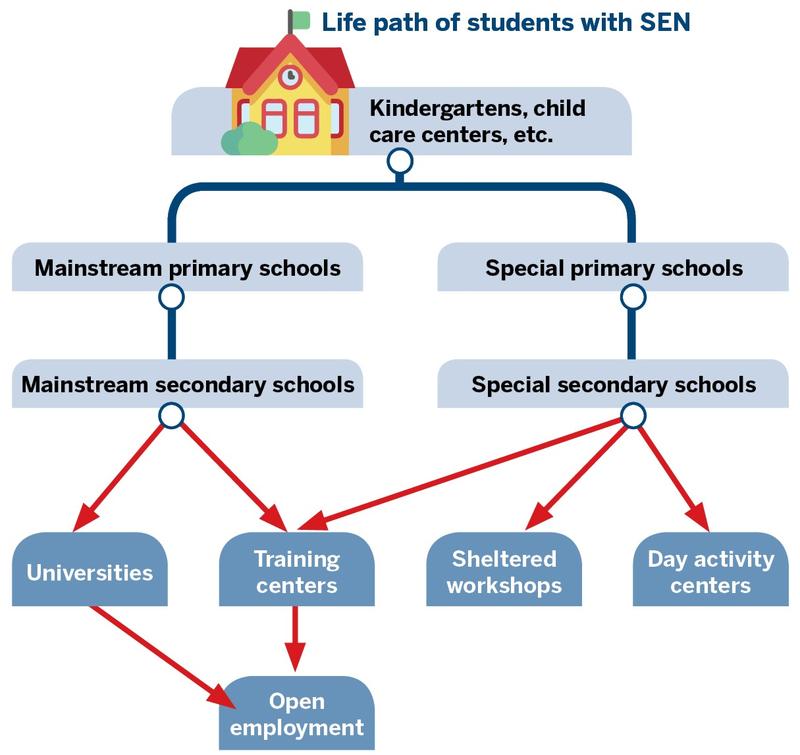

Hong Kong’s SEN students have equal opportunities to complete 12 years of primary- and secondary-level studies at school. They can attend special schools that are designed with their requirements in mind or select mainstream schools to help them integrate into society.

However, after graduation, their choices, based on their abilities, usually consist of day activity centers, sheltered workshops or vocational training centers.

Those who achieve high scores in the Diploma of Secondary Education exams can enter university. However, that has been rare in recent years: in 2019, more than 3,000 SEN students took the DSE exams, but only 43 were admitted to universities.

Those who are unable to live independently usually attend activity centers to receive daily care, while those who can care for themselves but are not qualified to work in wider society go to sheltered workshops that offer a protective environment. They get paid for doing easy work, such as packing goods alongside others with SEN.

People who can live and learn independently and pass the interview at the training center can be admitted for two or three years’ vocational training. They learn basic skills such as typing, packing and cleaning, then enter the workplace through open recruitment.

When they finish, the center matches them with jobs. For the past 50 years, such centers have been regarded as the best choice for SEN people because they can match them with jobs offered by the government or businesses, with the employment rate reaching 60 percent every year.

In Hong Kong, there are three training centers — the Caritas Lok Mo Integrated Vocational Training Center, the Hong Chi Pinehill Integrated Vocational Training Center and the Shine Skills Center — which help thousands of SEN students.

However, during the recent fifth wave of the pandemic, all the centers were closed and offline training was suspended.

Amid the economic downturn, which meant many SEN students could not receive training or find jobs, while those who had completed the training and entered the workplace were the first to be dismissed, Wallace Lau said.

Della Yang’s 21-year-old son Tsang Wai-yin, who has autism with mild intellectual disability, has only had one internship — working in a laundry for five days — during the past three years of vocational training at the Caritas Lok Mo center.

Before the pandemic started in 2020, Tsang went to the center five days a week, from 8:30 am to 4:15 pm, for a range of training sessions, such as cooking, cleaning, paperwork, baking and housekeeping.

Later, he took occasional classes, both online and offline, until the fifth wave struck the city at the end of last year. He was left with online training courses that required sustained practice, such as cooking.

Yang, who found it “ridiculous” watching Tsang take online cooking training, said SEN students need hands-on practice, and the online classes were less useful than watching related videos on YouTube.

Lacking cooking equipment and ingredients, most students could not follow the instructor to practice — they could only stare at the screen and zone out.

Tim Kwan, the occupational therapist at Tsang’s training center, blamed the economic downturn for the scarcity of internships and jobs for SEN students, saying they usually work in restaurants, hotels and theme parks, which have all been hit hard by COVID-19.

The center had partnered with Hong Kong Disneyland to provide internships and jobs, but that association was suspended when the amusement park had to close.

Before the pandemic, about 60 percent of the Caritas Lok Mo center’s students could get jobs, but that number fell to 40 percent in 2020 and then 20 percent in 2021, Kwan said. Nicky Chan, the center’s senior manager, has warned of a lingering impact, even when the pandemic stabilizes.

On April 25, the center resumed a half-day face-to-face training course and internship programs, plus job introductions for students.

However, many parents refused job opportunities as they thought their children’s training was inadequate and doubted their ability to enter the workplace. Now, there are concerns about a possible delay to student graduations.

The limited number of internships and job opportunities will become scarcer, Chan said, adding that the situation has created a backlog of students waiting for training, resulting in a vicious circle.

Plan B

The pandemic left the city’s social welfare network paralyzed, forcing the development of a “Plan B” for training centers, or possibly a better system in case the welfare system collapsed under a sudden social crisis, said Glendy Choi, whose 23-year-old daughter has autism.

The businesswoman was among those who refused to accept failure for their children, so she founded Learning Bridge, an NGO that aims to find jobs for SEN students.

Choi also plans to establish an operation named LBHub, an on-the-job, real-life workplace employing young people with SEN and focused on the digital workplace.

The employees will work in fields such as data processing, software or application testing and multimedia production, which are all practical skills in line that meet the needs of society.

“The current curriculum in vocational training centers for SEN students is in dire need of improvement,” Choi said.

When her daughter studied office skills at one of the centers, Choi was surprised to find that she was learning the Cangjie Input Method, a traditional way of inputting characters invented 50 years ago. It was the only method taught and used in the course.

In addition to skills training and work experience, LBHub will provide students with social and communications skills to improve their emotional readiness, with support and supervision from job coaches, social workers and counselors.

Choi understands that it will take time to reform the rigid skills-focused syllabus in the vocational training system. As the parent of a young person with SEN, she decided to use her own experience to help such people connect with society.

Wallace Lau suggested that parents should find new working styles for their children, rather than relying on the job market, even if that means becoming employers themselves.

In October, he started a studio to turn SEN students’ paintings and designs into products — such as backpacks, umbrellas and scarves — to improve their incomes and make their talents wider known. So far, hundreds of products have been sold.

Just one month after opening, the studio set up a booth at a trade fair in Kowloon. The three-day event was held to aid SEN students, with all 12 stalls operated by social organizations in fields such as hearing and speech impairments and intellectual disabilities. Wallace Lau’s booth welcomed more than 2,000 people and made HK$30,000 ($3,822).

Society and parents often expect nothing more from SEN students than for them to do simple work to integrate into the community, Wallace Lau said.

So, when the Education University of Hong Kong launched the first university program for SEN students, many parents hesitated to send their children, even though admission to the program only required an interview, without any DSE results.

More importantly, unlike training centers, the university doesn’t simply focus on vocational training and it has no responsibility to introduce students to job opportunities. After three years, they will still be on their own, very likely still unemployed.

For Wallace Lau, the job offers his son received were his answer to the other parents’ concerns.

“Improving ability is much more helpful than relying on social welfare in a society that follows the rule of natural selection and survival of the fittest. Moreover, ability is not just about vocational skill but comprehensive capability, including learning ability and personality,” he said.

Change in perception

Choi said, “Most employers have a limited understanding of the abilities and potential that young people with SEN can offer, resulting in the misallocation of resources in society.”

As someone who employs a person with SEN, she said their condition need not present a problem if their abilities are used in the right way.

Since the end of last year, Sunnie, a 26-year-old with autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, has been working at her NGO, helping with research and planning events.

Choi said Sunnie is diligent and never bored by repetitive work, such as data processing and desktop research, which other people may find dull.

Moreover, he is loyal to the company and values the job opportunity more than most people. He shows great passion for his work, even asking to bring work home when he was quarantined after a family member was diagnosed with COVID-19, Choi said.

Having worked in the commercial sector for many years, Choi said companies are business organizations that hire people to make a profit, so employing disabled people out of a sense of social responsibility is not sustainable.

To encourage the employment of disabled people, since Sept 1, 2020, the city government has granted eligible employers a maximum allowance of HK$60,000 for each disabled person they hire. The employee’s supervisor gets a bonus of HK$1,500.

Choi said the allowance is a good incentive for employers to take the first step toward giving jobs to people with SEN.

In the long run, it is the employers’ realization of the special abilities and potential of their SEN employees that will enable the creation of a truly inclusive workplace, she said.